Table of contents:

Introduction.

GDP growth and economic performance.

Inflation, monetary policy and credit conditions.

Domestic consumption and industrial output.

Real estate and debt issues.

Foreign exchange reserves and gold strategy.

Geopolitical realignment:

Shedding U.S. treasuries.

Dollar diversification, gold accumulation, and yuan internationalization.

BRICS+ expansion and alternative institutions.

Risks and vulneravilities:

Internal risks: Debt, demographics, and social stability.

External risks: U.S. sanctions, decoupling, and geopolitical flashpoints.

Before we begin, remember that if you’re accessing this article through the Substack app, you can listen to it instead of reading it. The MarketOps section is best suited for this format.

Introduction

China’s economy enters 2026 at a crossroads, with solid but moderating growth and an assertive shift in its global financial posture. Macroeconomically, China managed roughly 5% GDP growth in 2025 – a respectable pace supported by post-pandemic consumer recovery and policy stimulus. Inflation remains subdued (near 0% in 2025), enabling accommodative monetary policy, while authorities juggle challenges from a protracted property slump and mounting local government debt. Domestically, consumer spending and industrial output have rebounded from COVID lows, yet confidence is fragile amid soft employment and falling home prices. Beijing is striving to stabilize the vital property and infrastructure sectors without reigniting unsustainable borrowing.

On the geopolitical front, China is realigning its international financial engagements. It has reduced its U.S. Treasury holdings – now at a 17-year low below $700 billion – to mitigate exposure to U.S. financial leverage, especially after Western sanctions froze Russia’s reserves in 2022. Besides, China has accelerated diversification of its $3.36 trillion foreign reserves by accumulating gold and other real assets. The People’s Bank of China has been one of the world’s largest gold buyers, reflecting a strategic hedge against the dollar system. Beijing is also championing de-dollarization initiatives – from promoting the yuan in bilateral trade and swap lines, to leading alternative institutions (BRICS+, the Belt and Road Initiative, the AIIB) that offer parallel channels for trade and finance outside Western frameworks. These moves signal China’s intent to leverage its economic might to shape a more multipolar global order less dominated by the U.S. dollar and influence.

Check this for finding more info about real state in Asia:

The country remains as a growth engine with a large consumer market and technological ambitions, yet faces internal strains – high debt, an aging population, and imbalances in its growth model – as well as external risks from geopolitical tensions and decoupling trends.

GDP growth and economic performance

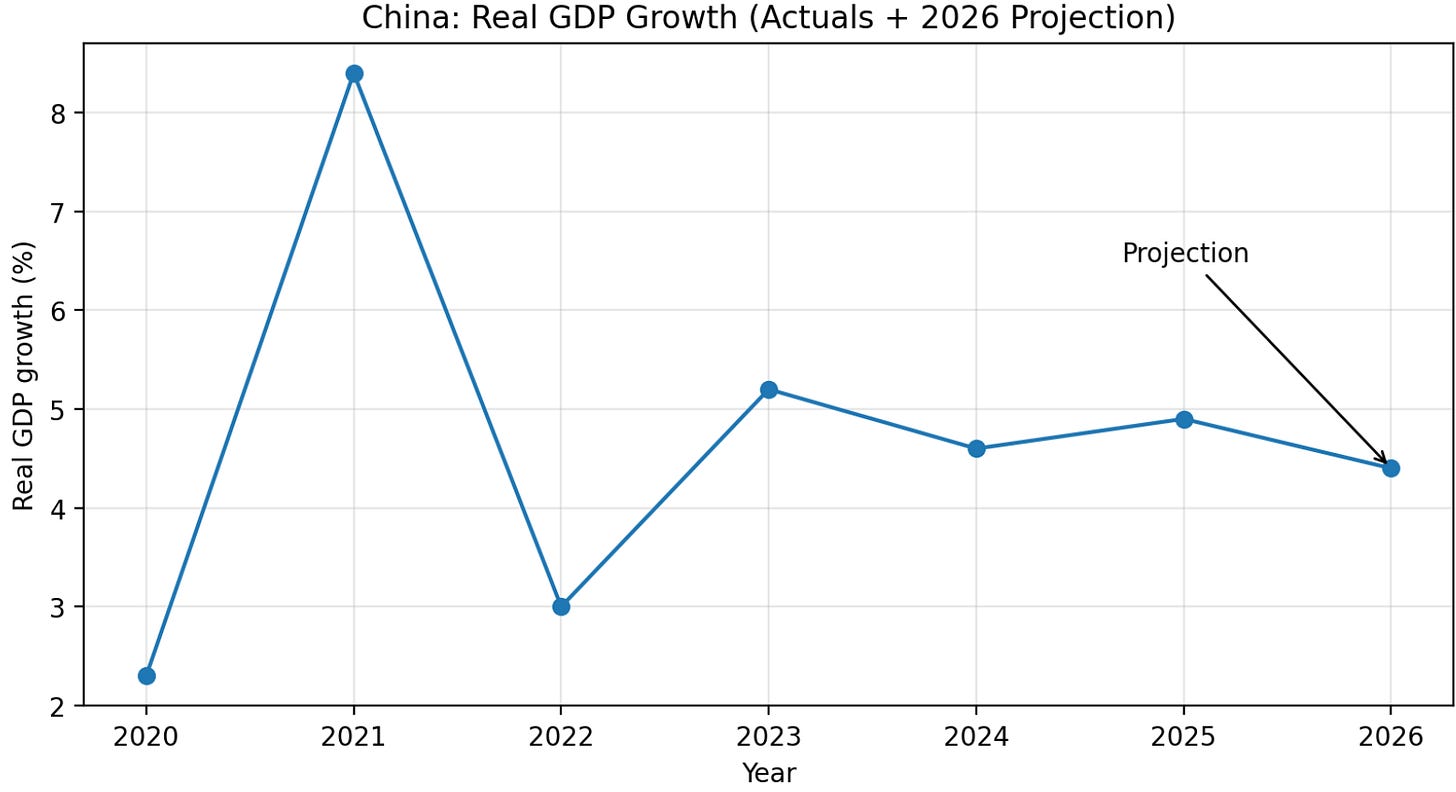

China’s growth trajectory in the mid-2020s reflects a balance of post-pandemic recovery and structural slowdown. After the pandemic shock of 2020 (when growth slumped to 2.3%), GDP rebounded by 8.4% in 2021 with the help of stimulus and base effects. However, momentum cooled to 3.0% in 2022. The lifting of COVID restrictions in late 2022 unleashed pent-up activity in 2023. China likely achieved around 5% GDP growth in 2023, roughly meeting Beijing’s target.

In 2024 and 2025, growth has settled in the mid-single digits. According to the World Bank, China’s year-to-date growth by Q3 2025 was 5.2%, and full-year 2025 growth is estimated at 4.9%. This marks a return to expansion, though notably below the heady ~7% rates of the 2000s and early 2010s. The downshift in China’s trend growth reflects structural factors as well as cyclical drags from weak property investment.

China’s recent growth has been driven more by domestic demand than exports. In 2025, consumer spending and services continued to recover, aided by accommodative policies and the end of COVID restrictions. However, consumers remain cautious. The World Bank notes households are reluctant to run down precautionary savings given a soft labor market and declining home prices. This caution is evidenced by high bank deposits and weak consumer confidence, a hangover from the pandemic and property downturn.

Government spending and infrastructure have also supported growth – Beijing leaned on a proactive fiscal policy in 2025, accelerating project approvals and special bond issuance to prop up investment. Meanwhile, net exports provided a smaller contribution amid slowing global trade, but demand from emerging markets (many of them BRI and BRICS partners) offered a buffer as developed-market demand softened. For 2026, the World Bank projects further easing to ~4.4% growth as property and external headwinds persist, barring more forceful stimulus.

Inflation, monetary policy and credit conditions

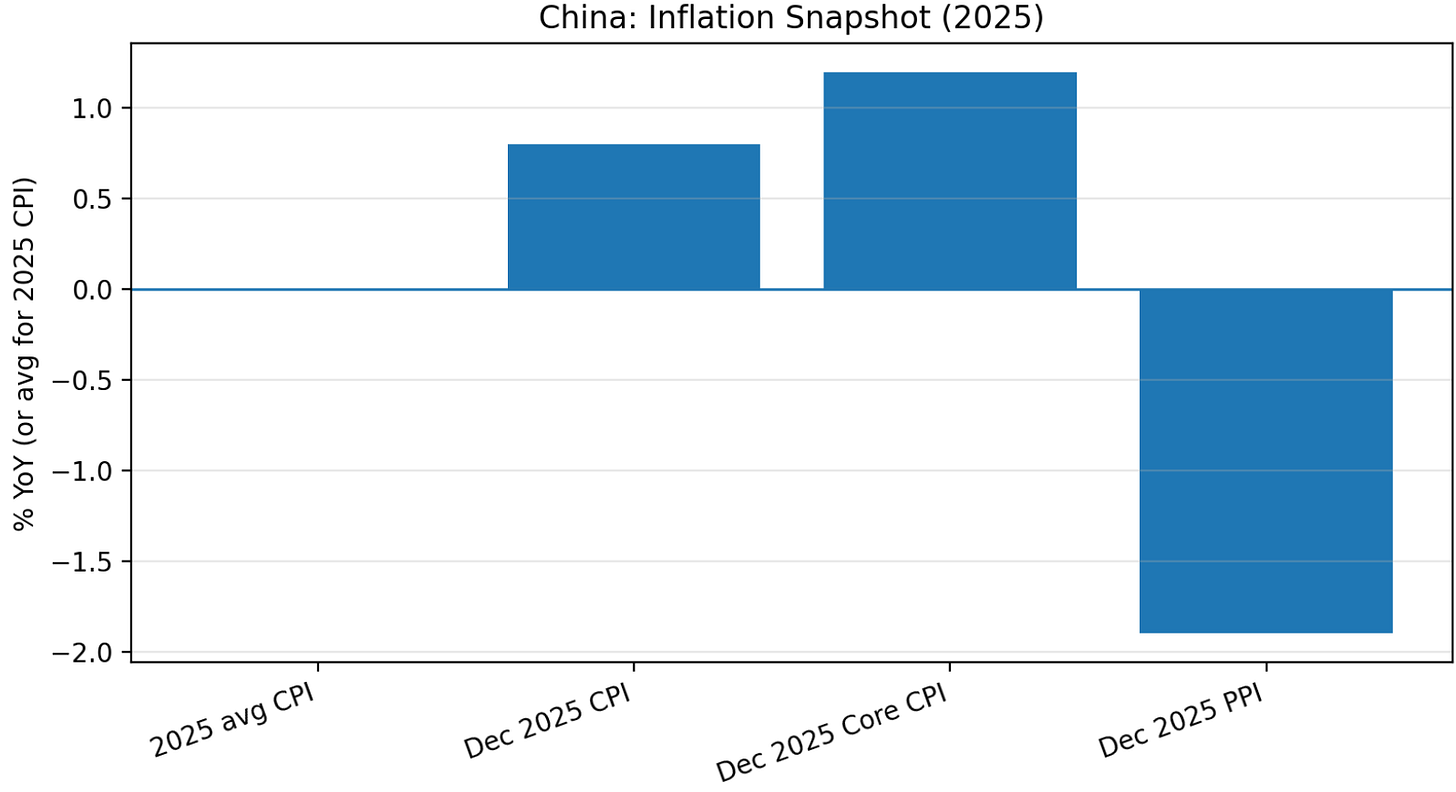

Inflation in China remains subdued, bordering on deflation for much of 2025. Consumer price inflation averaged 0.0% for full-year 2025, indicating essentially flat prices. Through most of 2025, monthly CPI prints hovered near zero, even dipping into mild deflation mid-year, before a modest uptick in the final months. By December 2025, CPI had risen only 0.8% year-on-year, the highest inflation rate in nearly three years but still low.

Core inflation (excluding food and energy) was a tame 1.2%. Meanwhile, producer prices have been in outright deflation for over three years. PPI in December 2025 was -1.9% YoY, reflecting persistently weak commodity and input prices. This prolonged low-inflation environment has at times raised fears of deflationary pressure akin to Japan, though recent data suggest the worst may be over – food prices have started rising again and the drag from falling pork prices is diminishing. Even so, inflation at under 1% is far below most countries, giving China’s central bank ample room to ease policy.

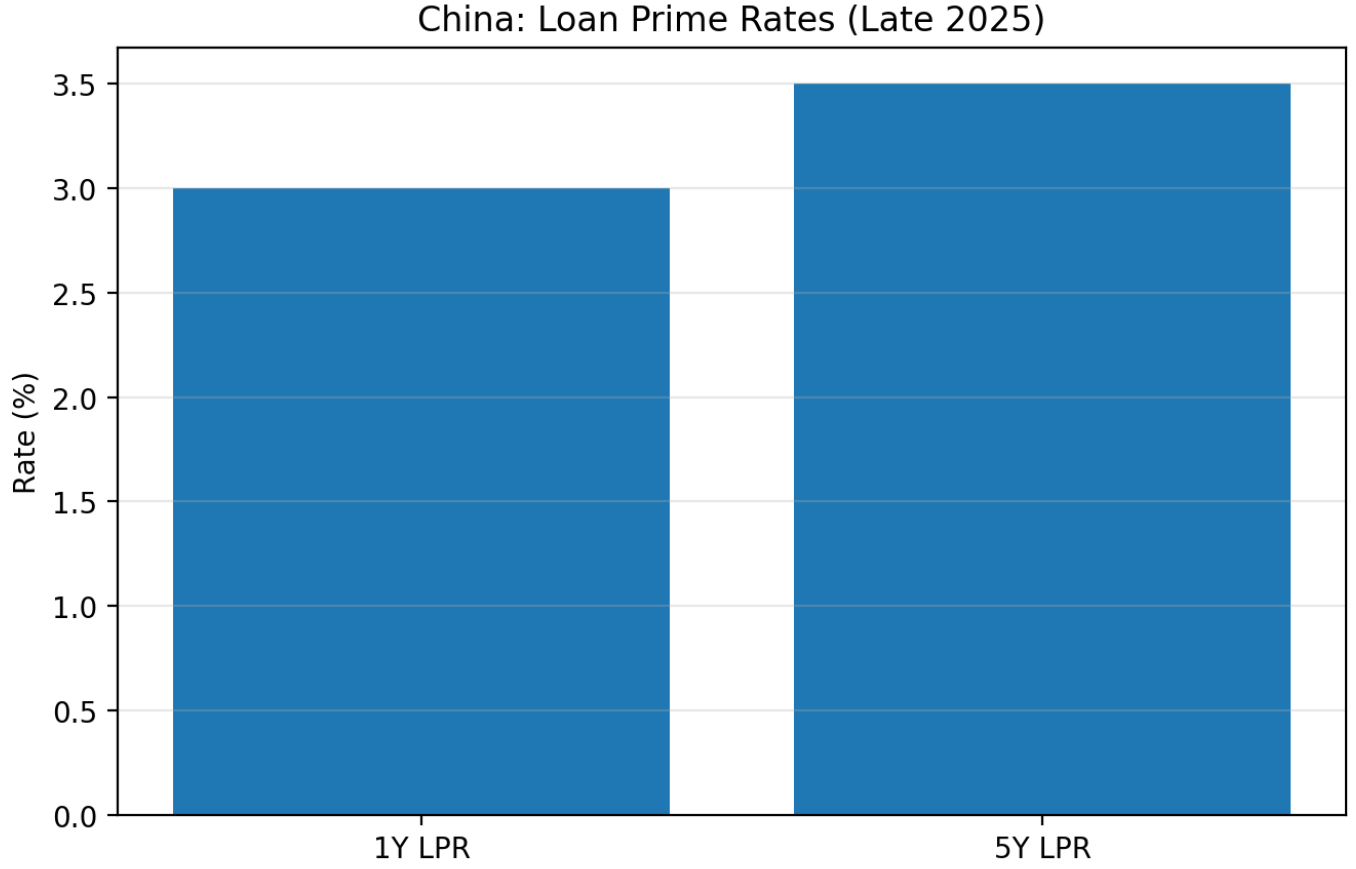

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has indeed maintained an accommodative monetary stance to support growth. Key benchmark rates are at or near record lows after a series of rate cuts in 2022–2023. In 2025, the PBOC shifted to a wait-and-see mode: it left the one-year and five-year Loan Prime Rates unchanged at 3.00% and 3.50% respectively for seven consecutive months through December 2025. Officials signaled that further easing will be deployed rather than in big bazookas, given that the economy was on track to meet the ~5% growth target without additional cuts.

Another factor for caution is bank profitability – with interest rates already so low, Chinese banks face margin pressure, and regulators must balance stimulus with financial stability. That said, guidance from China’s annual Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) in Dec 2025 was clear that monetary policy should remain supportive. Leaders pledged to maintain a proactive fiscal policy and emphasized growth stabilization and reasonable price increases as main considerations for monetary policy, hinting that they desire a bit more inflation after flirting with deflation. The CEWC also instructed the PBOC to flexibly and efficiently use tools like reserve requirement ratio cuts and interest rate cuts. Analysts accordingly expect modest easing in early 2026 to front-load support for government bond issuance and bolster liquidity.

Domestic consumption and industrial output

Domestic consumption has become pivotal for China’s growth, as external demand softens. After the lifting of COVID controls, household spending recovered in 2023–2025, led by services (travel, dining, entertainment) and an initial release of pent-up savings. Retail sales growth, however, began to stall by late 2025 as the post-reopening surge faded and consumers grew wary of falling asset values and job market uncertainty.

The labor market, particularly for youth, has been soft – urban youth unemployment hit record highs above 20% in 2023 before officials halted the release of the data. This job market strain, coupled with wage stagnation in some white-collar sectors, has made households more cautious. Indeed, high household savings are a double-edged sword: while they signal financial prudence and provide low-cost funding to banks, they also reflect weak consumer confidence, as noted by the World Bank.

Many Chinese families, worried about future income and lacking a strong social safety net, prefer to save rather than spend. This is compounded by the property slump eroding household wealth (housing constitutes roughly two-thirds of household assets). Thus, despite rising incomes and government consumption vouchers in some cities, consumer sentiment remains fragile. Auto sales and luxury goods saw mixed performance – new energy vehicle purchases were strong (boosted by subsidies and China’s push for electric cars), whereas sales of big-ticket appliances and premium brands were lukewarm. Going forward, boosting consumer demand is a policy priority. Beijing has signaled possible measures like improving social welfare (to reduce precautionary savings) and services sector support. Any sustainable rebalancing toward consumption will hinge on addressing the structural issues suppressing consumer confidence, from job prospects to the social safety net.

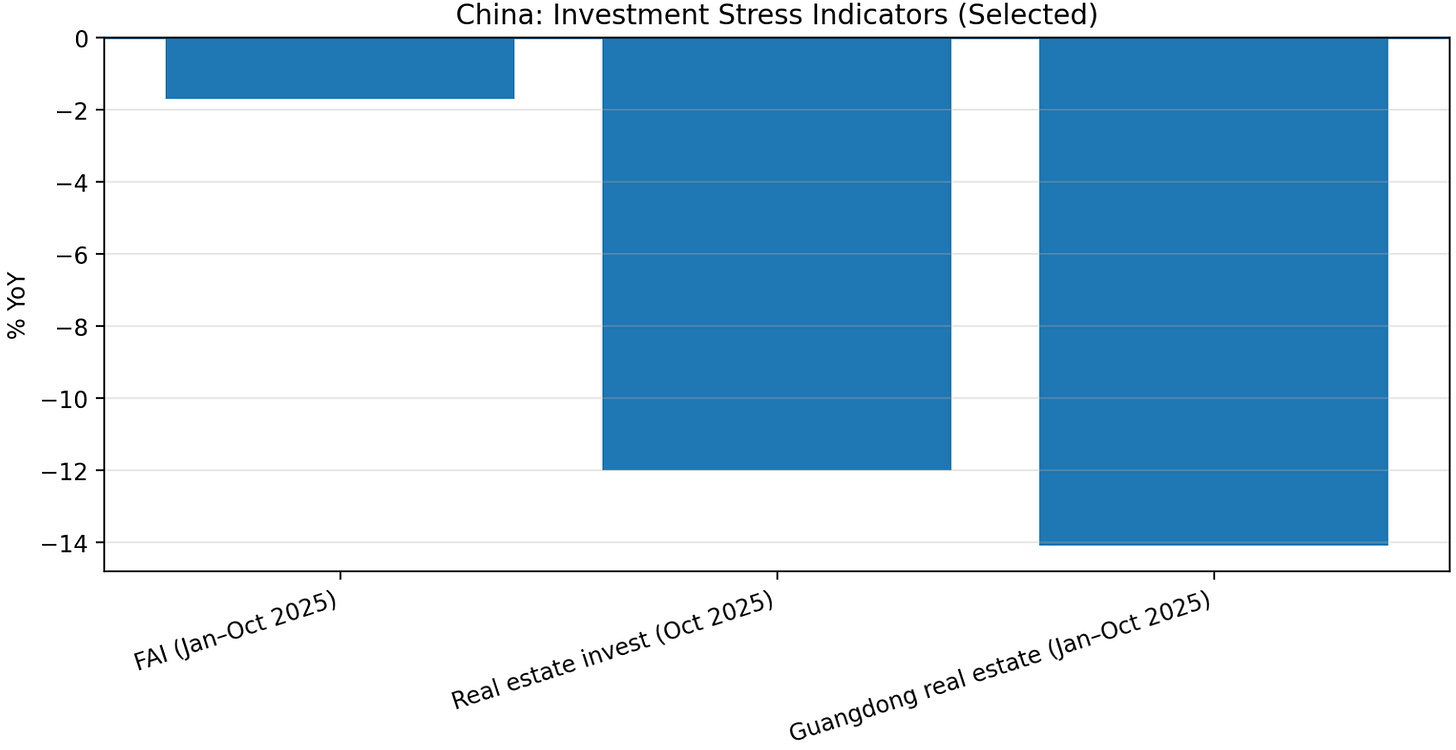

On the production side, industrial output has experienced a stop-and-go recovery. In 2023, factories ramped up production as China reopened, but by 2024–2025 industrial growth had downshifted due to weaker global demand and domestic investment curbs. By late 2025, China’s industrial sector was losing momentum – in November 2025, growth in factory output slowed markedly, reflecting soft export orders and energy/utilities output cuts. Heavy industries tied to construction (like steel and cement) are feeling the pain of the real estate downturn. Data underscore this weakness: fixed-asset investment (FAI), a key driver of industrial demand, has been contracting. From January to October 2025, overall FAI was down 1.7% year-on-year, with an even sharper -12% YoY drop in the month of October by some estimates. This is unprecedented in recent years – it marks the first sustained decline in national FAI since at least 2020.

Manufacturing investment and private sector investment have been weak, squeezed by thin profits and uncertainty. Even infrastructure spending has slowed as local governments grapple with funding constraints. Regionally, China’s powerhouse provinces saw steep investment declines – e.g. Guangdong’s investment plunged 14.1% YoY in the first three quarters of 2025. Much of this industrial and investment slowdown traces back to the property sector correction and the associated debt clean-up. With property developers cutting new projects and local governments swapping debt instead of launching new ventures, demand for machinery, materials and intermediate goods has slackened. The manufacturing PMI indices in late 2025 oscillated around contraction territory, showing fragile business confidence.

Despite these challenges, certain industrial sectors remain bright spots. High-tech manufacturing (such as electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels) continues to grow at double-digit rates, fueled by domestic and export demand, as well as supportive industrial policies. China’s output of NEVs and renewable energy equipment has surged, making it a top exporter in those categories.

Defense-related manufacturing and semiconductor fabrication equipment are areas seeing increased state-led investment as China prioritizes self-sufficiency amid tech tensions. Export-oriented factories have had to adapt as well: while exports to the U.S. and EU were sluggish (due to trade tensions and slowdowns there), China has increased exports to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, often as part of BRI projects or trade agreements. This helped keep overall exports resilient in 2025 despite headwinds. All told, China’s industrial sector is at an inflection point – traditional smokestack industries tied to property are contracting, while new strategic industries rise. Policymakers are cognizant of this divergence and are redirecting credit to strategic manufacturing. The challenge for 2026 will be to prevent a deep industrial slowdown by stabilizing investment (especially in housing and infrastructure) without abandoning the deleveraging of unproductive debt.

Real estate and debt issues

China’s real estate sector – long a pillar of growth – is in the midst of a painful correction that has broad impacts on the economy and financial system. Following decades of booming construction, home prices and property sales began falling in 2022–2023 as developer debt stress came to a head. By 2025, the property downturn had become a major drag on growth and a source of financial risk. Property investment has contracted for over two years, and residential real estate prices have declined, eroding household wealth. The crisis of private developers like Evergrande and Country Garden – which defaulted on debts after years of aggressive leverage – has led to numerous stalled projects and shaken buyer confidence.

New housing starts and land sales (a key revenue source for local governments) are at multi-year lows. The government has responded with a flurry of measures to stabilize housing demand: cutting mortgage rates, lowering down-payment requirements, easing home-purchase restrictions in many cities, and nudging banks to extend credit to finish unfinished projects. These steps have had only a muted effect so far – sentiment remains weak as potential buyers fear further price drops and developers struggle with liquidity. The property sector’s woes are rippling through the broader economy, impacting everything from steel demand to local government finances and consumer psychology (since roughly 70% of urban household wealth is in housing). The World Bank warns that challenges in the property sector and related subdued earnings prospects are a key downside risk to China’s outlook.

Closely intertwined with the property slump is China’s debt overhang. Years of credit-fueled growth have pushed total debt (government, corporate, household) to over 280% of GDP, by some estimates. In particular, local governments and their financing vehicles (LGFVs) amassed enormous off-balance-sheet debt during the infrastructure and property boom. As land sale revenues collapsed (down sharply due to the housing downturn), many local authorities found themselves in fiscal distress, struggling to service debts and even cutting civil servant pay or delaying public services payments.

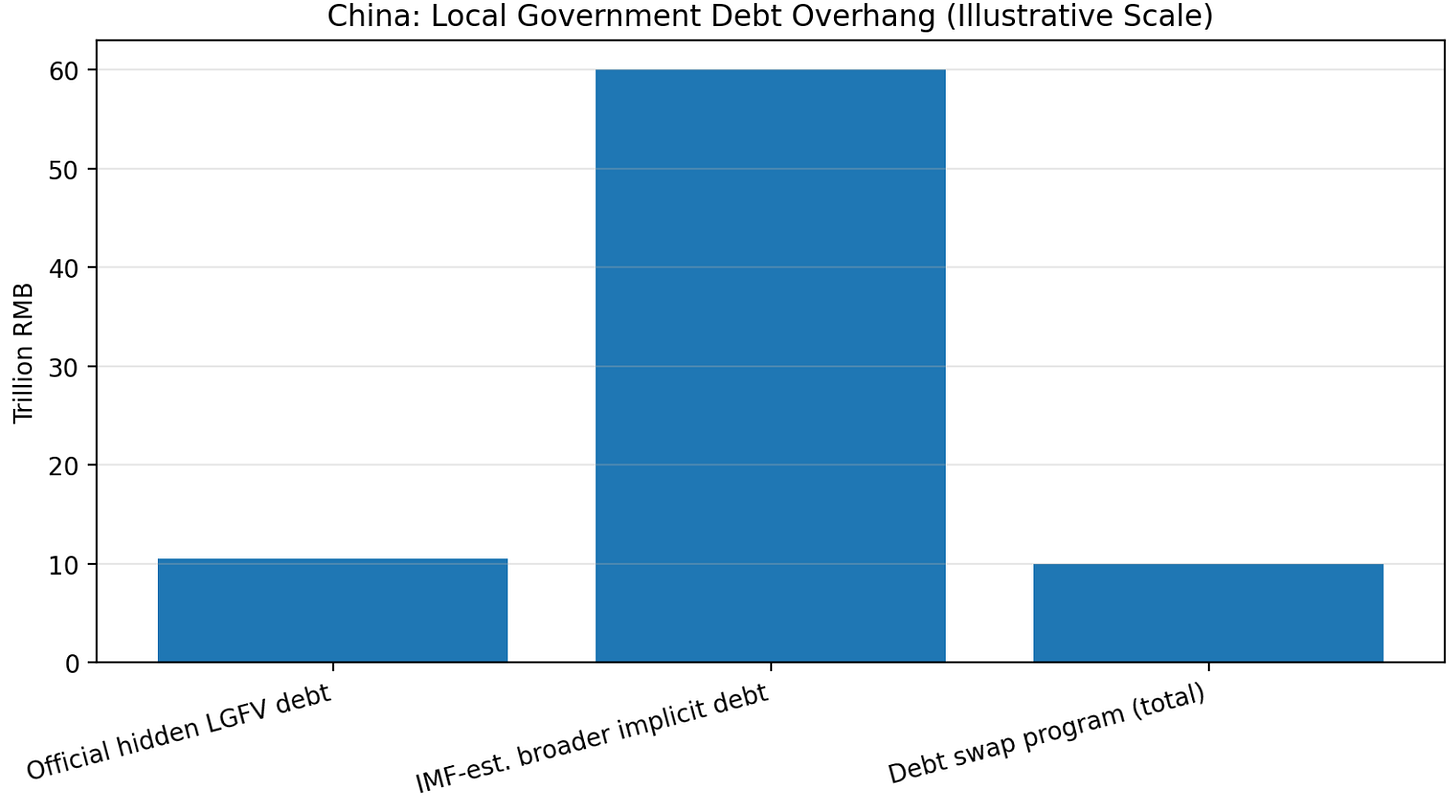

In response, Beijing launched a massive debt-resolution campaign in late 2024, approving a ¥10 trillion ($1.4 trillion) debt swap program to help provinces refinance hidden debts. Under this scheme, from 2024–2026 local governments can swap ¥2 trillion per year of shadow LGFV debt into official bonds, and additionally use special bonds for debt reduction. While this provides temporary relief, the scale of the problem is daunting. Officially reported hidden debt (mostly LGFV obligations not on government books) was ¥10.5 trillion as of end-2022. But IMF estimates peg local hidden debt at a staggering ¥60 trillion by end-2023 – roughly 48% of GDP. This implies much of the local debt burden remains unaddressed even after the swap program.

The consequences are apparent: throughout 2025, local governments diverted a large portion of new bond issuance toward refinancing instead of new investment. In the first 10 months of 2025, local governments issued ¥9.1 trillion in bonds (a record), but an estimated 60% of that went to repay existing debt rather than fund new projects. This extend and pretend approach – rolling over debts to buy time – has suppressed infrastructure spending, contributing to the aforementioned investment slump.

From a financial stability perspective, banking sector risks have risen due to real estate and local government exposure. Many regional banks and state banks have large loans to developers, LGFVs, or mortgages. Rising bad loans in those segments are pressuring bank capital. So far, a systemic crisis has been averted – regulators have encouraged loan restructurings and tapped policy banks to support troubled developers – but credit conditions are tight for property firms and LGFVs, as markets anticipate further defaults and haircuts.

Some high-profile developers underwent restructuring in 2025 (e.g. Evergrande’s offshore debt plan faltered amid regulatory troubles). The government has had to walk a fine line: pushing banks to extend credit to the property sector (to prevent collapse) while simultaneously signaling that housing is for living, not speculation and avoiding a re-inflation of the bubble. The downside risks are that a deeper property correction could threaten financial stability and local governments’ ability to function.

On the upside, authorities still have tools: the central government balance sheet is relatively healthy (central government debt is < 40% of GDP) and could backstop local debts if needed. Indeed, top officials assert that government debt risks are manageable and within a reasonable range, signaling willingness to intervene if contagion looms.

Foreign exchange reserves and gold strategy

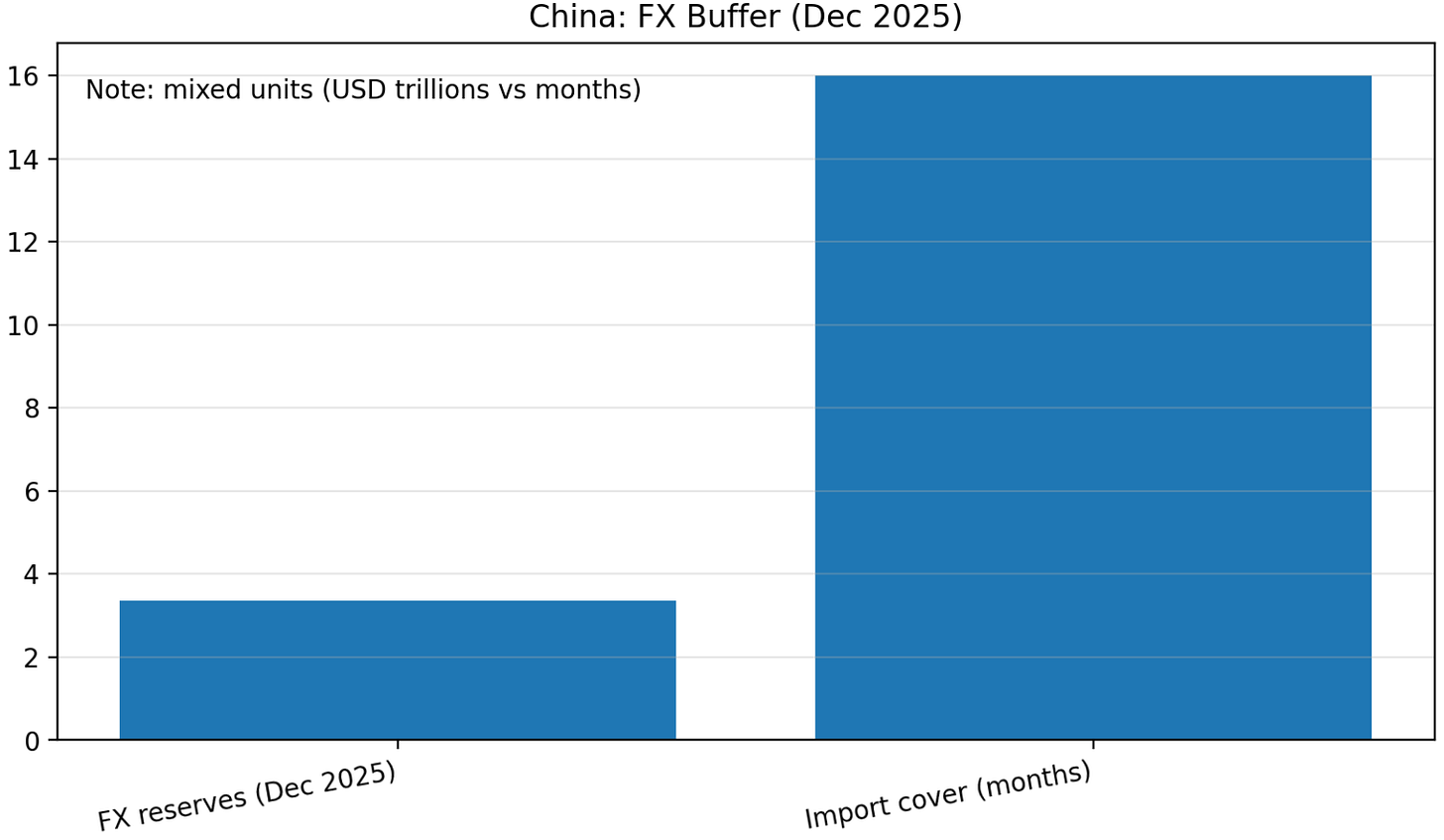

China commands the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves, and it has been strategically reallocating those reserves in light of geopolitical and market shifts. As of December 2025, China’s FX reserves stood at $3.358 trillion, slightly up from a year earlier. The increase in 2025 was modest (about $40 billion year-on-year), reflecting valuation effects (e.g. a weaker dollar in late 2025 boosting non-dollar assets) and China’s continued trade surpluses.

The composition of reserves has been gradually shifting. Over the past decade – and accelerating in recent years – China has reduced its holdings of U.S. Treasury securities in favor of other assets like gold and euros. In October 2025, China’s U.S. Treasury holdings fell to $688.7 billion, the lowest level since 2008. This is less than half of China’s peak U.S. Treasury stash (about $1.32 trillion in 2013), illustrating a significant diversification away from U.S. government debt. As of 2025, China has slipped from the largest foreign creditor of the U.S. to the third place (after Japan and, recently, the UK). This drawdown of Treasuries has been deliberate and sustained – it began around the time of the U.S.-China trade war (2018) and continued through the Trump and Biden administrations.

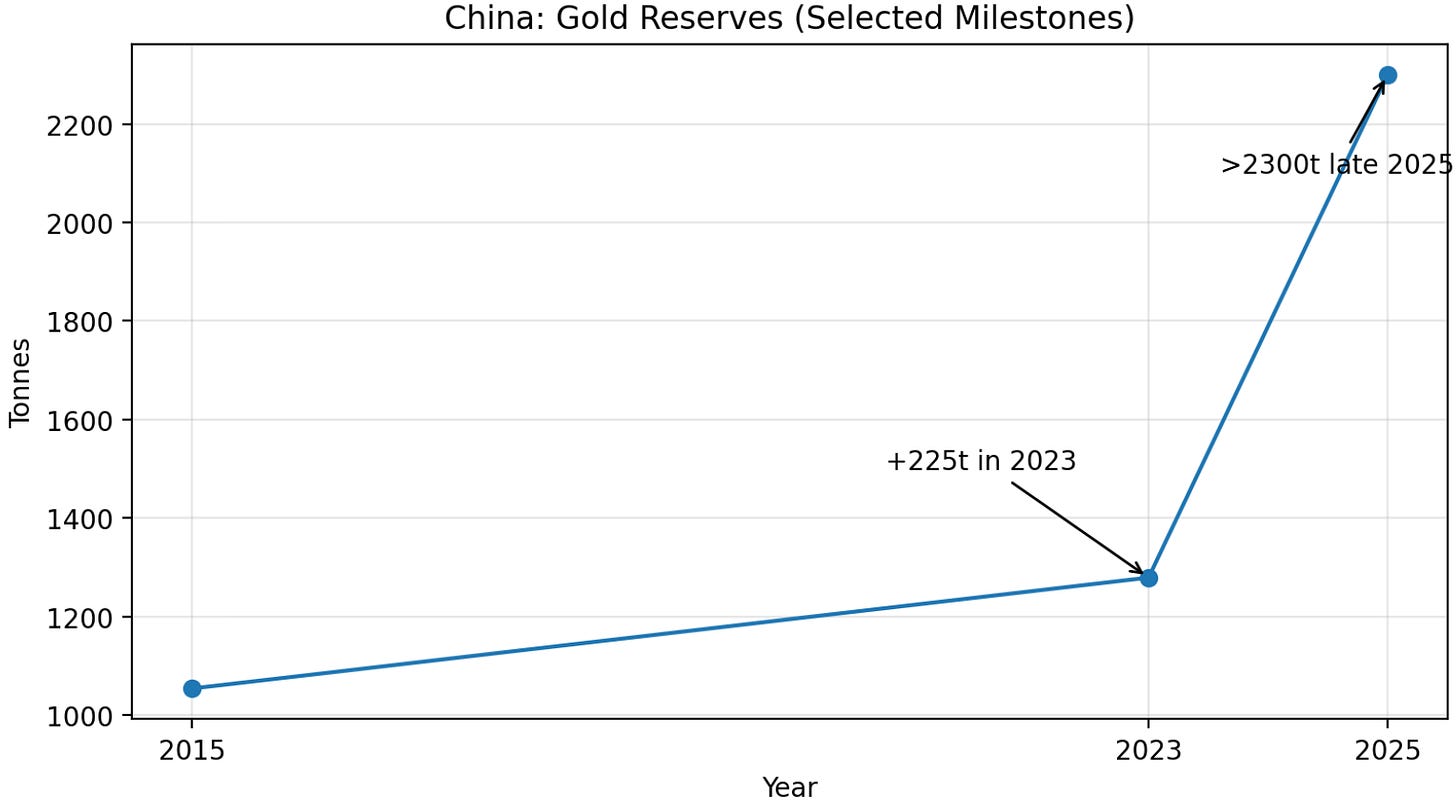

China has pursued an aggressive gold accumulation strategy as part of its reserve diversification. The People’s Bank of China quietly rebuilt gold reserves from around 1,054 tonnes in 2015 to over 2,300 tonnes by late 2025.China added 225 tonnes of gold in 2023 alone, making it the world’s largest official sector gold buyer that year. Purchases continued in 2024 and 2025 (including 21 tonnes in the first eight months of 2025). Gold now constitutes a much larger share of China’s reserves than it did a decade ago. By value, at end-2025 China’s gold hoard is worth roughly $150+ billion (with gold prices hitting record highs around $3,500/oz in 2025). The motivations are clear: gold is a tangible asset not tied to any one country’s currency, a hedge against dollar depreciation and geopolitical risks.

The freeze of Russia’s US dollar reserves in 2022 deeply resonated in Beijing. Chinese policymakers took note that in extremis, only holdings of gold (and perhaps other non-Western assets) would be fully secure. Indeed, when Russia was sanctioned, it was left able to access only its yuan assets and domestic gold while its dollar and euro reserves were locked. China is determined to avoid a similar vulnerability. A former PBOC advisor, Yu Yongding, even warned in late 2025 of growing risks tied to US dollar assets and advocated reducing such holdings.

In internal discussions, Chinese officials have argued that as the world’s second-largest economy, China’s gold reserves should be at least 5,000 tonnes – roughly aligning with China’s economic size relative to U.S. gold holdings (8,133 tonnes). While official targets are not disclosed (and China may also be acquiring gold through state banks or proxies off the books), the trend is unmistakable: Beijing is steadily bulking up on bullion. This has global implications – central bank gold buying (led by China, Russia, and others) has been a factor driving gold’s 40% price surge in 2025.

Beyond gold, China’s reserve managers have diversified into other currencies and assets. The euro, Japanese yen, British pound, and others likely make up larger shares of the portfolio now than a decade ago. China has also increased holdings of IMF Special Drawing Rights after the RMB’s inclusion in the SDR basket and the IMF’s 2021 SDR allocation. Furthermore, sovereign bonds of European and Asian countries, as well as equities and alternative assets through state investment arms, are all part of China’s broader national forex holdings (though the SAFE (State Administration of Foreign Exchange) portfolio is opaque). Another notable trend is China’s buildup of strategic commodity stockpiles (oil, metals) – while not reserves in the traditional sense, these physical stockpiles act as a buffer and are sometimes financed via reserve usage (for instance, buying cheap oil when prices dipped).

China’s foreign reserve strategy is now driven by a dual mandate: safety/liquidity versus geopolitical security. U.S. Treasuries, while liquid and safe in credit terms, carry rising geopolitical risk for China. Beijing has trimmed those holdings, even at the cost of foregoing some interest income or market liquidity, in order to reduce exposure to potential U.S. financial sanctions or dollar instability. The freed-up capital has been redirected into assets that Beijing views as strategically valuable: physical gold, critical commodities (copper, lithium, rare earths) and overseas infrastructure investments. By doing so, China not only diversifies its national wealth but also secures inputs for its economy and deepens economic ties with resource-producing countries.

For investors, China’s reserve shifts are a barometer of a changing global financial order. Diminished Chinese demand for U.S. Treasuries could put upward pressure on U.S. interest rates over time, and it signifies a fragmentation of reserve holdings globally (indeed, the share of USD in global reserves has fallen to its lowest in 25+ years). Meanwhile, China’s voracious gold buying lends long-term support to precious metals. Understanding these trends is key to anticipating central bank actions and currency movements in the new geopolitical landscape.