Table of contents:

Introduction.

Software vs. manufacturing.

The Meta-Google alliance.

Circular revenue and regulation.

The 2026 macroeconomic regime.

Strategic portfolio rebalancing.

Specific risks and rebalancing triggers.

Introduction

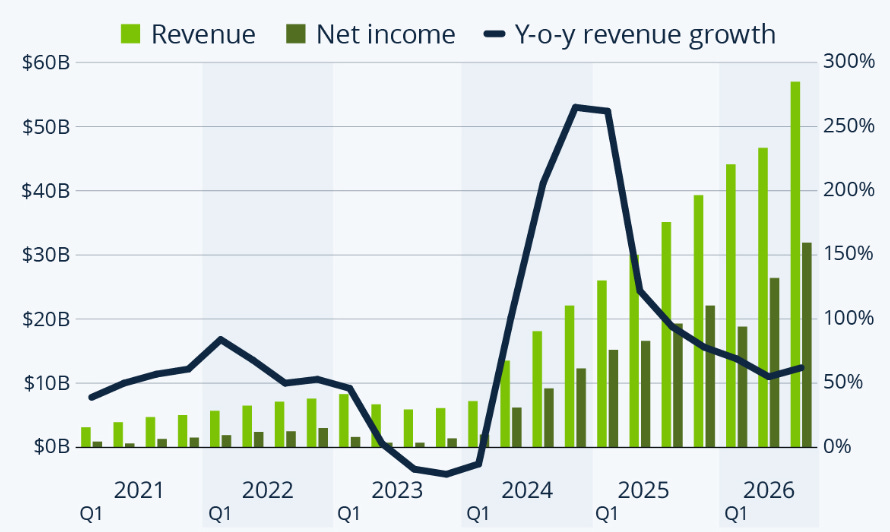

As we cross the threshold into 2026, the global financial markets are waking up from a collective fever dream. For the better part of three years, the investment world has been held captive by a singular, intoxicating narrative: that the exponential scaling of Artificial Intelligence would detach economic value from physical constraints, ushering in an era of infinite, high-margin growth. This belief system, which drove the Mag 7 to dizzying valuations, was predicated on the assumption that the laws of software economics—zero marginal costs and infinite replicability—could be magically applied to the grinding, capital-intensive world of hardware manufacturing.

That narrative has now collided with the hard walls of reality.

The Factory Valuation Fallacy, a concept we introduced as a contrarian warning in early 2025, has metastasized into the primary driver of market volatility. Investors who aggressively capitalized hardware manufacturers at 40x sales—mistaking the production of H100 GPUs for the shipping of code—are now witnessing a brutal reversion to the mean. The reality of late 2025 is stark:

The AI hardware sector is not a software business; it is an industrial one, bound by the unforgiving mechanics of supply chains, yield rates, and raw material costs.

Check more about the competition of AI infrastructure here:

However, the valuation disconnect is merely the symptom of a deeper structural rot. Beneath the surface of soaring stock prices lay a fragile ecosystem built on circular revenue—a closed-loop financing scheme where venture capital dollars were round-tripped through cloud commitments to manufacture the illusion of organic demand. As the Securities and Exchange Commission launches a record number of enforcement actions into AI washing and revenue recognition, the regulatory risk premium has returned with a vengeance. The market is beginning to realize that the supply-side gluttony of the last cycle—the massive overbuilding of capacity for end-users that do not yet exist—has created a supply glut that will take quarters, if not years, to digest.

Compounding this microeconomic crisis is a hostile macroeconomic regime shift. The 2026 outlook is defined not by the disinflationary tech boom of the 2010s, but by a stagflationary reality shaped by aggressive tariffs, persistent core inflation, and a Federal Reserve handcuffed by fiscal dominance. In this environment, the scarcity that matters is no longer digital; it is physical. We have moved from a market valued in tokens and parameters to one constrained by megawatts and tonnage.

The following analysis details why the most asymmetrical opportunities for 2026 lie not in the chips themselves, but in the copper that transmits their data, the uranium that powers their training runs, and the steel that frames their data centers.

Software vs. manufacturing

The primary intellectual anchor of our bearish stance on the semiconductor sector in early 2025 was the “Factory Valuation Fallacy.” The market had aggressively assigned software-like multiples (30x-50x sales) to hardware manufacturers like Nvidia, operating under the delusion that the marginal cost of producing an H100 or Blackwell GPU was negligible, comparable to shipping a line of code.

The reality of late 2025 has dismantled this assumption. Unlike software companies, which benefit from near-zero marginal costs of replication, the AI hardware sector has collided with the hard walls of physics and supply chain logistics. Nvidia’s gross margins, which peaked near 76% in the height of the mania, showed clear signs of compression in Q3 FY2026, retracting to 73.4% on a GAAP basis. This contraction is not a temporary blip but a structural mean reversion caused by rising input costs, specifically in High Bandwidth Memory and advanced packaging.

The argument presented by Michael Burry—that valuing a factory like a tech company leads to inevitable capital destruction—has proven prescient. Burry, who liquidated his hedge fund Scion Asset Management in November 2025 to launch a dedicated advisory newsletter, has highlighted supply-side gluttony as the cardinal sin of the current cycle. The massive overbuilding of capacity, incentivized by peak margins, invariably leads to a glut. We are now witnessing the early stages of this glut in the logic chip market, even as shortages persist in memory and power.

Google doesn’t buy chips to increase productivity; they buy them to own the pickaxe factory. This observation has manifested literally. In 2025, the hyperscalers (Google, Microsoft, Amazon) ceased to be merely customers of the pickaxe makers and became competitors. Google’s aggressive commercialization of its TPUs, culminating in the rumored multi-billion dollar deal with Meta in November 2025, signifies that the largest buyers of AI silicon have successfully vertically integrated. They are no longer renting the factory; they have built their own.

This shift erodes the moat that investors believed protected Nvidia. The assumption was that the CUDA software ecosystem created insurmountable lock-in. However, the sheer scale of the hyperscalers allows them to bypass CUDA entirely by optimizing frameworks like PyTorch and JAX for their own silicon. As Google offers its TPUs to third parties like Anthropic and Meta, the premium that the market is willing to pay for merchant silicon must collapse.

The Meta-Google alliance

The single most consequential market development of Q4 2025 was the revelation by The Information and subsequent market corroboration that Meta Platforms is in advanced negotiations to procure Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) for its next-generation AI training clusters.

This development is catastrophic for the infinite growth narrative of the incumbent chip leaders for several reasons:

Volume displacement: Meta has historically been the single largest purchaser of Nvidia GPUs, with its Llama models trained on clusters of H100s numbering in the hundreds of thousands. A diversification into TPUs represents billions of dollars in revenue actively migrating away from the incumbent monopoly.

Validation of ASICs: By adopting Google’s custom silicon, Meta validates the Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) pathway over the General-Purpose GPU pathway. ASICs, designed specifically for matrix multiplication in transformers, offer superior performance-per-watt—a critical metric as energy constraints tighten.

Google as a vendor: This deal marks Google’s transition from a cloud service provider to a merchant silicon vendor. Executives at Google Cloud reportedly estimate they can capture up to 10% of the AI chip market revenue, essentially siphoning growth from the current leaders.

The market reaction was immediate and violent: Nvidia stock retreated while Alphabet shares surged toward a $4 trillion valuation, creating a divergence in the Mag 7 that actively penalizes pure-play hardware exposure while rewarding integrated infrastructure ownership.

While the spotlight has been on logic chips, a more acute crisis has emerged in the memory sector. The demand for High Bandwidth Memory (HBM3e and HBM4) to support AI accelerators has monopolized foundry capacity, crowding out production for standard DRAM and NAND used in consumer electronics and conventional servers.

Data from late 2025 indicates a staggering 171.8% year-over-year increase in DRAM contract prices, with consumer DDR5 module prices quadrupling in some regions. This is a classic bullwhip effect:

To secure HBM for AI, manufacturers like SK Hynix and Micron diverted wafer capacity away from commodity DRAM.

The consequence is a shortage of standard RAM has hit the PC and smartphone supply chains. Retailers like CyberPowerPC have announced price hikes, and availability is rationed in markets like Japan.

This inflationary pressure acts as a tax on the entire hardware ecosystem. It compresses margins for system integrators (Dell, HPQ) and slows the replacement cycle for consumer devices, creating a stagflationary headwind for the broader tech sector.

The release of Google’s Gemini 3 on November 18, 2025 , and Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5 on November 24, 2025 , highlights a disturbing trend for the “AI Bull” thesis: diminishing returns on capital.

While Gemini 3 and Opus 4.5 are technically superior to their predecessors, the wow factor has dissipated. The leap in utility for the average enterprise user is marginal compared to the exponential increase in compute cost required to train and run these models. The market is realizing that while reasoning capabilities have improved, the revenue generated per token has not kept pace with the CapEx per token.

Furthermore, the commoditization of the models themselves is accelerating. With open-weights models (like Meta’s Llama series) trailing closed models by only months, the ability for any single AI lab to maintain a durable competitive advantage is eroding. This shifts the locus of value capture away from the model creators (OpenAI, Anthropic) to the application layer (Palantir) and the infrastructure layer (Utilities, Data Centers).

Circular revenue and regulation

A central pillar of the 2024-2025 bull market was the closed-loop financing ecosystem, or round-tripping. In this scheme, a tech giant invests venture capital into a startup, which then signs a cloud commitment returning that capital to the investor as revenue.

How does it work? Nvidia or Microsoft might invest in a cloud service provider like CoreWeave or a model builder like OpenAI. These entities then use the cash to buy H100s or Azure credits. The money effectively moves from the left pocket to the right pocket, creating the appearance of explosive organic growth.